Disclaimer – although the facts and arguments below are well researched, this blog post is not meant to be used as anything other than a short introduction to a very complex episode in Roman history. Students are therefore strongly discouraged from referencing this blog post in their work but are invited to use it as a springboard into the subject. A select bibliography is available at the end of the post.

A Brief History of Gaius’ Career

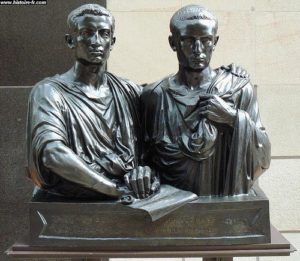

At the time of his brother’s death, Gaius Sempronius Gracchus was still too young to hold even the most junior of offices but in 126 BC he successfully stood for election to the quaestorship in his own year – that is in the very year when he was old enough to satisfy the minimum age requirement for that office. He served his term in Sardinia, where he won great renown for his administrative skills and general great ability. Wary of his popularity, the Senate sought to keep him away from politics by extending the Sardinian governor’s term of office. This would usually have meant that the governor’s staff, including Gaius as his quaestor, would have stayed behind with him. Gaius, however, left for Rome at the end of his original term in time to submit his candidacy for the election of the tribunes for 123 BC.

The Senate tried to halt his progress by prosecuting Gaius for abandoning his post and his governor but he defended himself expertly, arguing that he and the governor held different offices independently and that he could be replaced by one of the newly elected quaestors. Once this hurdle had been cleared, Gaius stood for election and, thanks to the combined influence of his own personal ability and of his brother’s service to the people, was immediately elected to the office. Gaius would make wise use of his brother’s career, often reminding the assembly of the sacrilegious murder of Tiberius by a patrician and shaming the people for how they stood by and did nothing to save him.

According to Appian’s history of the period, Gaius’ tribunate in 123 BC was largely uneventful except for one major bill that saw the institution of a monthly ration of free state-sponsored grain for every citizen of Rome. This policy, which was upheld for the remainder of Roman history, would become one of the main burdens on the Roman treasury.

At the end of his tribunate, Gaius was reluctant to stand for a second term and, in fact, he did not contest the elections for 122 BC. Whether this was a personal choice or whether he was wary of antagonising the Senate as his brother had before him by standing for a second tribunate is not clearly known. Either way, his retirement was very brief since he was automatically elected to the tribunate when not enough candidates reached the required quota for election. Gaius, therefore, found himself once more before the public assembly and this time he would truly bring his influence to bear.

In the decade since Tiberius’ death, the equestrian order, an unoffical rank between the senatorial class and the poor of Rome that was extremely active in the commercial sphere, had become increasingly politically conscious, spurred on by what they interpreted as unfair treatment by the senatorial class and the latter’s exclusive monopoly on actual power.

Seizing the opportunity presented by recent cases of obvious senatorial corruption in the law courts, Gaius Gracchus passed a bill transferring control of the courts to the equestrian class. By doing so, he not only drastically reduced the actual power of the Senate and won the support of the equestrian class, but he also allowed for the equestrian class to be seen as a social class in its own right as opposed to its previous status as an intangible intermediary class between two extremes. This class would yield such names as Gaius Marius and Marcus Cicero in the following decades.

Confident in his position thanks to the support of both the lower classes and the equestrian order, Gaius embarked on a bold plan that saw the commissioning of new roads, public works, and colonies, including one on the site of Carthage. In a more daring move, Gaius also proposed the extension of all Roman citizenship rights to Latin allies and the eventual extension of voting rights to all Italian allies. Although any move in favour of the Italian allies had been met by very staunch opposition in the past, the bill seemed to be about to pass thanks to Gaius’ widespread support. The Senate, therefore, instructed one of their own men on the bench, Livius Drusus, to veto the bill. He quickly followed up the veto with a bill proposing even more colonies than Gaius had, swinging the lower classes to his side.

Following this political setback, Gaius Gracchus and Fulvius Flaccus, a consul and close supporter of Gaius, left for Africa to oversee the setting up of the new colony at Carthage. In the meantime, the Senate and their supporters ran a highly effective smear campaign against Gaius in Rome. The Carthage colony, called Iunonia, was crippled by alleged bad omens and the Senate threatened to abrogate the bill providing for its foundation. Gaius and Fulvius returned to Rome to oppose the abrogation and gathered the assembly on the Capitol.

According to Appian, an ordinary citizen by the name of Antyllus approached Gaius Gracchus and sought to dissuade him from using force. A supporter of Gaius then misinterpreted Gauis’ sharp reaction as an instruction and stabbed Antyllus where he stood. The news of the assault caused a mass stampede as the people assumed that major violence had broken out. Gaius and Fulvius attempted to quiet down the situation by addressing the people in the forum but their attempts were ineffective and they both retired to their own homes.

The other consul, Opimius, called up armed forces and summoned the Senate to the Temple of Castor and Pollux, from where they eventually summoned Gaius and Fulvius to explain themselves. Distrusting the Senate, however, the two gathered their own supporters and seized the Aventine hill. Attempts at reconciliation by proxy were refused by the Senate, which then passed a Senatus Consultum Ultimum, a decree calling upon the leaders of the State to use whatever means necessary to quell an obvious danger to the Republic. Opimius instructed his own personal bodyguard of Cretan archers to surround the Aventine and cut down the Gracchan supporters. Gaius committed suicide while Fulvius was captured and beheaded.

And so, the second Gracchus suffered a similar fate to that of his brother and became the subject of equally divided judgment.

Champion of the People or of the Middle Class

Gaius’ motivations have been interpreted differently by different authors and historians throughout the ages. Some have seen him as a brother who went into politics to safeguard the work of his brother or to seek revenge for his brother’s sacrilegious murder. Others believe him to have been genuinely motivated by a wish to participate in politics, still the most prestigious occupation for a Roman gentleman, and possibly genuinely motivated to help the worse off in Roman society. Yet others would focus on the different policies pursued by the same person in his two terms of office and interpret that as a sign of gradually changing aspirations.

The grain ration bill was certainly aimed at supporting the poorest of Rome’s citizens, for whom Tiberius’ land bill did not manage to secure land allotments. The policies pursued in Gaius’ second term in office, however, were less geared towards the plight of the common man and directed more strongly towards extending his support base among the middle class. While the building projects he authorized would provide for short-term employment for the lower classes, they would certainly facilitate trade for the merchant class and for the first time in Roman history, commercial potential became a major consideration in the placement of colonies. The sites chosen by Gracchus for his colonies were not only fertile enough for agriculture but were also situated along major trade routes and were meant to house more people than the surrounding land could potentially support agriculturally. Of course, trade ventures would have provided the people in these colonies with alternative employment in the ports, warehouses and on deck, but their consideration marked a break from previous policies that sought to make colony communities self-sufficient. Moreover, the same jobs related to commerce could very easily have been given to slaves, as they indeed often were.

The transfer of the composition of the court juries from the senatorial to the equestrian class was also to no benefit to the common man on the street, as the equestrians were as likely to be dismissive of the poorer citizens’ plight as the senators were, and indeed they had very quickly sided with the Senate against Tiberius’ land reform bill, albeit with no success.

It is hard to say what Gaius intended to do with his widespread support. His support of the Latin and Italian communities would have further increased his support base but that doesn’t in itself explain why he would go out of his way to antagonise sections of his already loyal support base to reach out to communities who would probably not have been able to come to Rome to vote on a regular basis anyway. Perhaps Gaius was setting the stage for more extreme bills in the future of which he made no public mention before his death, or perhaps he was truly aiming for the crown, as some had alleged of both him and his brother before him.

A House Divided

One of the more glaring consequences of the Gracchan period is that a division within the senate-house itself started to become increasingly apparent. While Tiberius had had his own supporters on the Senate floor, Gaius was supported throughout by a consul of the Republic. An ever-clearer division appears between senatorial “Optimates” and “Populares”. The “Optimates” were senators who believed that good government was one dictated by the senatorial class and applied by magistrates acting on the advice of the Senate. The “Populares” argued for rule through the popular assemblies, emphasising the sacred sovereignty of the Roman people. While the divisions were not always clear-cut and it was not uncommon for politicians to change sides in their career, the rest of Roman history can easily be discussed in terms of a struggle between Optimates and Populares.

The Equestrian Order and the Courts

Originally, the equestrian order referred to all those Roman citizens who could afford to keep a horse and who therefore served as the cavalry of the Roman army. Over time, as Rome prospered and the citizen population grew, the number of equites swelled considerably and the equites became an unofficial class as wealthy as the senatorial class, if not more, but with far less political rights.

One of the main concerns of the equites was that the senatorial class supplied all the jurors and magistrates of the law courts and it was glaringly obvious that the courts were very ready to pardon members of their own class but condemn equites for the same crimes and with the same evidence. By transferring control of the courts to the equites, Gaius Gracchus effectively turned the table on the senatorial class. Bias against senatorial defendants became as glaringly obvious as bias against the equites had been in the preceding years and control of the courts would become a major point of contention for rival politicians in the decades to come.

It is reported that when the law had only just been passed Gracchus said tmhat with one blow he had laid low the senate, and as its effects unfolded the truth of his assertion became ever more apparent. For the fact that the equestrians sat in judgement of all Romans and Italians, and on the senators themselves, with the widest jurisdiction over property, civil rights, and eile, set them up as virtual rulers over the senators, who thus became no more than their subjects… Before long it came about that dominance in the state had been reversed, the senate possessing now only the prestige, but the equestrians the power.

Appian, The Civil Wars, 1.22

More importantly, however, by setting aside particular offices for the equestrian order, Gaius Gracchus gave the equestrian order a tangible political presence that led to the class being more officially recognised and targeted by politicians in subsequent electoral campaigns. The political recognition of this new political class changed the political landscape and forced a change in the rhetoric and policies that had been championed for time immemorial.

The political homogeneity of the equites can, however, be overemphasised. While in the immediate decades following the Gracchan reforms, the equites were more often than not seen as a bulwark against senatorial power, not all equites would have sided with the Populares, and quite a few held very strong Optimate sympathies. The initial strong anti-senatorial sentiment immediately following the Gracchan period yielded such equite politicians as Marius, but the more conciliatory equites of the post-Sullan period lent their support to milder politicians such as Cicero, who distrusted the demagoguery of the Populares.

A more detailed history of the composition of the law courts deserves its own consideration in the future.

The Italian Question

Rome’s Latin and Italian allies enjoyed special and differing relations with Rome and were all expected to supply soldiers for Rome’s wars. Despite their loyal service, they received very few of the benefits of the Roman citizenship, were excluded from voting and suffered much when the commission set up by Tiberius Gracchus confiscated public land used by them for redistribution among Roman citizens.

Following the suspicious circumstances of Scipio Aemilianus’ death in 129 after he had sought to champion the Italian cause, Gaius’ bill might have been seen by a weary Italian community as an attempt at rapprochement and, if successful, it could have encouraged greater peaceful cooperation throughout the peninsula. As it turned out, the bill’s defeat and the failure of Marcus Livius Drusus’ bill calling for the extension of the citizenship in 91 (this Drusus was, rather ironically, a relative of the Drusus that had vetoed Gaius’ citizenship extension bill) further eroded Italian trust in their Roman allies and contributed to the tensions that caused the outbreak of the Social War in 90BC.

The Senatus Consultum Ultimum

Gaius Gracchus’ career saw the first true use of the Senatus Consultum Ultimum (henceforth, SCU), a decree of the senate akin to a modern declaration of a state of emergency. Some authors have argued that the SCU was first used against Tiberius Gracchus but it should be noted that Scipio Nasica’s episode lacks one very important element – the endorsement of the consuls. Back in 132, the consuls had refused to take action, maintaining that that would be an unnecessary violent escalation and that they could cancel Tiberius’ bill as “passed by violence and against the auspices” later on. This time round, the motion was not only passed by the Senate but enforced by an actual military force – as opposed to Scipio’s bunch of haphazard supporters – led by a consul of the Republic.

The legality of the SCU is dubious. In the first place, the Senate itself did not actually have the power to pass legislation but could only expect to give advice on new laws. Whatever authority the Senate commanded was due to their influence and prestige and not constitutional law – a weakness that Tiberius’ career had highlighted. Moreover, it was unclear what it was actually meant to do. In essence, it seems to ask the consuls to raise forces to ensure the security of the Republic. The consuls’ office itself allowed the holders to raise forces on behalf of the Roman people anyway, and the fact that Opimius had a personal bodyguard numbering in the hundreds ready at his command suggests that he was either planning to use force anyway or that the tensions were so high that rival factions were arming up already.

After the Gracchi

Following the bloodshed, Opimius was quick to perform purification rites in the city and the Senate instructed him to build a temple to Concord in the Forum. With both Gracchi dead and the tribunes in disarray, the Senate saw to it that a bill was passed allowing for the redistributed land to be sold, leading to the re-amassing of land in the hands of the rich and reversing the progress the land commission had done. Soon after, another tribune was prevailed upon to pass a bill cancelling all rent owed for public land, a move disguised as a bill to unburden the small-scale land owners of dues to the state but effectively meaning that the very rich who owned most land did not need to pay for their use of huge tracts of profit-generating public land. The free grain rations for each citizen continued and remained a huge burden on the public treasury, a situation worsened by the cancellation of the rents on public land.

The Gracchi had shown the power that a popular tribune could wield and following politicians exploited this new avenue for power and the new middle class expertly.

In the coming issue, we will take a closer look at the history of the career of Marius, with particular emphasis on the role that powerful tribunes and the Optimates-Populares divide played in making him such a central role in Roman politics.

Suggested reading:

– Plutarch, Lives of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus

– Appian, The Civil Wars, Book 1. 21-27

– Beard, M. (2015) SPQR – A History of Ancient Rome, Chapter 6: New Politics

– Beard, M. and Crawdord, M. (1999) Rome in the Late Republic, 2nd ed. London: Bloomsbury [this book considers the various changes that led to this point in history and determined the decades following from it. The book espouses a thematic approach that considers the problem on a cultural, an economic, and a socio-political level]

– Kondratieff, E. (2003) Popular Power in Action: Tribunes of The Plebs in The Late Republic. Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania,

– Maddox, G. (1982) ‘Responisble and Irresponsible Opposition: The Case of the Roman Tribunes’ in Government and Opposition, Vol. 17

– Scullard, H. (1982) From the Gracchi to Nero, 5th ed. London: Routledge

– Steel, C. (2013) The End of the Roman Republic – 146 to 44 BC, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Resource Highlight

The online youtube Channel Extra Credits uploads regular weekly videos on various historical periods. In 2016 Extra History released a number of videos on the careers of the Gracchi brothers. The videos, available here, are an excellent way to revisit the history of the period and are a perfect way to make history come to life in your lessons. Happy viewing!